In China, you can buy a heavily discounted “used” electric car that has never, in fact, been used. Chinese automakers, desperate to meet their sales targets in a bitterly competitive market, sell cars to dealerships, which register them as “sold,” even though no actual customer has bought them. Dealers, stuck with officially sold cars, then offload them as “used,” often at low prices. The practice has become so prevalent that the Chinese Communist Party is trying to stop it. Its main newspaper, The People’s Daily, complained earlier this year that this sales-inflating tactic “disrupts normal market order,” and criticized companies for their “data worship.”

This sign of serious problems in China’s electric-vehicle industry may come as a surprise to many Americans. The Chinese electric car has become a symbol of the country’s seemingly unstoppable rise on the world stage. Many observers point to their growing popularity as evidence that China is winning the race to dominate new technologies. But in China, these electric cars represent something entirely different: the profound threats that Beijing’s meddling in markets poses to both China and the world.

Bloated by excessive investment, distorted by government intervention, and plagued by heavy losses, China’s EV industry appears destined for a crash. EV companies are locked in a cutthroat struggle for survival. Wei Jianjun, the chairman of the Chinese automaker Great Wall Motor, warned in May that China’s car industry could tumble into a financial crisis; it “just hasn’t erupted yet.”

To bypass government censorship of bad economic news, market analysts have opted for a seemingly anodyne term to describe the Chinese car industry’s downward spiral: involution, which connotes falling in on oneself.

What happens in China’s EV sector promises to influence the entire global automobile market. China’s emergence as the world’s largest manufacturer of EVs highlights the serious challenge the country poses to even the most advanced industries in the U.S., Europe, and other rich economies. Given the vital role the car industry plays in economies around the world, and the jobs, supply chains, and technologies involved, the stakes are high.

But the wobbles in China’s EV sector demonstrate the downside of China’s state-led economic model. China’s government threw ample resources at the EV industry in the hopes of leapfrogging foreign rivals in the transition to battery-powered vehicles. The Center for Strategic and International Studies estimates that the government provided more than $230 billion of financial assistance to the EV sector from 2009 to 2023. The strategy worked: China’s EV makers would likely never have grown as quickly as they have without this substantial state support. By comparison, the recent Republican-sponsored tax bill eliminated nearly all federal subsidies for EVs in the U.S.

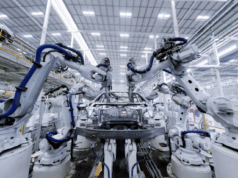

The problem is that China’s program encouraged too much investment in the sector. Michael Dunne, the CEO of Dunne Insights, a California-based consulting firm focused on the EV industry, counts 46 domestic and international automakers producing EVs in China, far too many for even the world’s second-largest economy to sustain.

Dunne told me that the EV sector in China is consolidating; 11 Chinese companies now dominate the local car market. But the industry should probably shrink further. The capital-intensive car business relies on economies of scale, which is why the world has so few major automakers.

Yet China’s auto industry is still nascent enough to attract new players, including major electronics companies. Xiaomi, which makes everything from smartphones to rice cookers, launched its first EV model just last year. To woo customers in this crowded market, China’s EV companies have been slashing their prices, making profits slim.

In most economies, the market would sort out this mess by culling the weakest players. But China’s leaders don’t trust markets to achieve their national goals, so they readily intervene. In China, state support or ownership of automakers extends the life of struggling businesses. Local governments are also reluctant to lose the jobs they bring, so officials prop up unprofitable companies. The city of Wenzhou recently helped arrange financing for an EV maker called WM Motor, to get the company’s local factory humming again. The city of Hefei rescued the EV start-up Nio in 2020, but the publicly listed company continues to lose money—$1.6 billion in the first half of this year.

China’s EV woes are a direct consequence of these interventions, which have engineered an unsustainable glut of vehicles. But instead of addressing these market problems, China’s leaders are cracking down on what they call “disorderly competition,” such as the aggressive EV price war and the sale of zero-mileage “used” cars.

Beijing has its own reasons to avoid the economic reforms that would make its EV industry more viable. By keeping factories running, even at a loss, the government can shore up an economy plagued by sluggish consumer spending and a slumping property market. More important, EV makers are a key part of Beijing’s plan to expand China’s global power.

China’s state-led EV program, by design, has been predatory. By subsidizing these companies, China sought to edge out more established automakers in the U.S., Europe, and elsewhere. Beijing’s economic planners are willing to sacrifice something as frivolous as profitability to fulfill their dreams of building an internationally competitive car industry. China “sustains a lot of inefficiency at home in order to dominate industries and markets globally,” Dunne told me.

Yet even the Chinese state may not be able to prop up its automakers indefinitely. The research firm Rhodium Group figures that Chinese policy makers spend the equivalent of 3 percent of the central government’s fiscal revenues to subsidize car sales. Gregor Sebastian, a senior analyst at Rhodium, told me that this level is probably unsustainable, particularly if the Chinese government also hopes to develop semiconductors and AI. He recommends that Chinese policy makers “slowly take the foot off the gas pedal, but in a way that the sector doesn’t collapse.”

China’s EV industry’s gains in the international market are also under threat. President Joe Biden’s administration imposed a 100 percent tariff on Chinese EVs last year, which President Donald Trump has maintained, effectively shutting these vehicles out of the U.S. market. The European Union, Canada, Turkey and Mexico have also hiked duties on Chinese cars. Restricted access to key international markets could make it even harder for Chinese EV companies to survive without aid from their government.

The international automobile industry is shaping up to be a test of wills between the Chinese leaders determined to dominate it and the global policy makers who hope to stop them.

This contest isn’t all bad. By pushing down car prices, China’s policies may benefit consumers worldwide. But China’s state-led economic model still comes at a high cost, given the ways its huge subsidies and low prices are forcing governments around the world to use tariffs to meddle with the markets. China’s distorted EV market now threatens to hoard industry jobs by making it impossible for any car company to turn a profit. In the end, China’s EV industry may overrun its competitors, but still be a financial catastrophe.