Summary

- The EU automotive sector is part of the identity of Europe as an industrial player. It is also central to the future of innovation, from robotics to AI, and pivotal for the green transition.

- Central and eastern Europe’s dense network of thousands of tightly connected businesses in this sector is deeply integrated with the German economy.

- German carmakers were early—and highly successful—entrants to the Chinese market. As global trade frictions grow and Chinese firms become highly competitive internationally, German auto companies are investing more in China, likely at the cost of central Europe and their own suppliers at home.

- The central and eastern European industrial network risks atrophying or becoming a collection of Chinese assembly lines as firms in China begin to open up operations inside the EU to avoid tariffs.

- If Europe wants to maintain a role as an industrial powerhouse, policymakers must discard outdated ideas of “competitiveness”. German and central European leaders should create attractive conditions for companies to double down on the existing industrial network. They must work across borders to save jobs, avert social strife and ensure that European industry can also withstand the second “China shock”.

Escape forward

For decades, the performance of Germany’s economy—Europe’s largest—has been fuelled by selling goods to China. This export-orientated approach was essential to the German industrial-led economic model. But those times are over and Berlin now faces a dilemma.

The world has been hit by two “China shocks” since the turn of the millennium. The first followed China’s accession to the World Trade Organization in 2001, when Chinese-made consumer goods began to flood global markets and displaced manufacturing jobs, particularly in the US. Meanwhile, after the end of the cold war, central and eastern Europe provided a skill-rich, relatively low-wage neighbourhood that suddenly became available to the German economy. Thus, during the first China shock Germany benefited from deep integration with markets in central and eastern Europe—and from its complementarity with a Chinese economy to which high-quality German products and technology transfer were extremely valuable.

This time around, the second China shock is going to harm Germany and its neighbours, potentially very seriously. To compensate for low consumption at home and as part of its national security-driven economic dominance strategy, China engages in predatory trade practices. The colossal Chinese economy exports massive overcapacities of advanced manufactured goods to the world. But these goods are no longer the cheap electronics, washing machines and textiles of 25 years ago; complementarity is a thing of the past. Chinese goods now compete directly with Germany’s core industrial sectors. Current trends have the potential to dissolve Germany’s industrial backbone, including first and foremost its car industry.

Because of Germany’s deep integration with its neighbours, the ramifications of the second China shock will be widely felt. Direct trade between central and eastern Europe and China is comparatively low. But central and eastern European countries are wrapped tightly into German supply chains (and with each other). For years, these countries’ governments have been looking for a sweet spot: attaching themselves to competitive German global value chains, while cosying up to China for additional economic benefits. Yet central and eastern European leaders still fail to grasp that this China shock will be bruising for Germany—but fatal for them.

Europeans are not defenceless against this looming, higher-end industrial competition with China. They can strengthen existing industrial clusters to protect German-central and eastern European value chains and the jobs and livelihoods that depend on them. Germany and central and eastern European states should work together to de-risk from China and reindustrialise their economies. In preparation for a new era of “system competitiveness”, they should build on the strengths they developed during the first China shock and work collectively to weather the effects of the second.

This policy brief identifies the dangers facing the central European industrial heartland. These dangers include industrial atrophy in which core industries simply die off; and “sinicisation” in which Chinese firms take over production on European soil, providing limited local benefit and ducking the impacts of defensive EU trade policy. These twin dangers arise from decisions made in China—but also in European capitals and the head offices of major European companies. This paper explains how decision-makers in the countries of this industrial heartland can “escape forward”. It provides a vision for a new trade and economic reality in which Europe remains competitive and resilient to coercion.

From national competitiveness to system competitiveness

Germany’s new chancellor, Friedrich Merz, has said that every decision taken under his leadership will be judged on its impact on industrial competitiveness: Europe must be “prepared to step into the next phase of competitiveness”. The goal? To compete in a liberal, free market of globalised value chains that drive down the cost of products for consumers and enhance profits in advanced economies.

This is the world of “level playing fields” with China; “improving European innovation” is the mantra. Political leaders’ discourse is preoccupied with notions of Europe spending more money, becoming more efficient and enhancing the framework conditions for its companies—to keep up with Chinese industries in key sectors, if not outcompete them.

But that is not what the past 15 years of economic interaction with China suggest. Europeans are not up against Chinese businesses—they are up against the strategic ambitions of the Chinese Communist Party, which wields the collective financial firepower of the world’s second-largest economy.

China’s expansion is driven by potent, subsidised industrial policy ecosystems—from innovation to manufacturing and through securing a global footprint. Chinese firms’ advantages in Europe are only going to become more biting as these firms eat away at parts of the European economy. Vital sectors of the European economy are on the verge of being hollowed out, eradicated completely or taken over by Chinese competitors.

Europe collectively has leverage, power and agency to address this—as long as its leaders recognise that the old economic model has come to an end and they need to shape a new one. If the challenge is not about Europe helping its companies become competitive, it is about Europe itself becoming system-competitive. In this new reality, the ability to produce industrial goods is essential. To achieve this, Europeans need to rethink their approach to competitiveness—by placing industrial strategy at the heart of it.

The rise of the central European industrial heartland

The central European industrial network flourished over the last three decades. It combines German industrial strength with the flexibility and competitiveness of central and eastern Europe. This spontaneous, transformational and business-driven process started immediately after the fall of the Berlin Wall and took off at an unprecedented pace right after the EU’s 2004 “big bang” enlargement. It was particularly driven by German policy, which pursued an economic model of export-led growth and benefited from manufacturing capacities in countries like the Czech Republic, Hungary, Lithuania, Poland, Romania and Slovakia. German investment flowed into these countries and helped create a dense collaborative network with local suppliers. The result was a fairly coherent regional value chain that became an economic force to contend with.

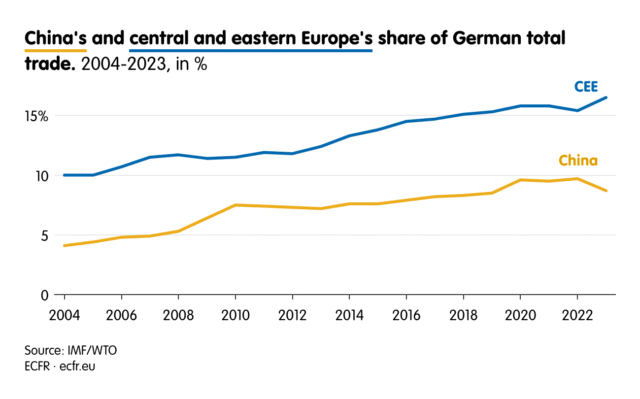

It is hard to overstate the economic importance to Germany of its central and eastern European neighbours. With more than half a trillion dollars of bilateral trade ($522bn in 2023),[1] together they dwarf any single individual trade partner for Germany, including China. Germany and its corporates were by no means the only players to benefit from central and eastern European industrial prowess and competitiveness, but they were certainly the most important in terms of trade and establishing local production through foreign direct investment. This is not merely a “hub-and-spoke” story of individual countries’ bilateral trade with Germany, but a true network channelling trade in the region, with components and goods crossing borders multiple times.

This ever-closer integration enabled the central European industrial network to compete on the global stage. A vast, flexible and cost-competitive supply network helped German companies withstand not just the first China shock but also build resilience for subsequent economic challenges during the eurozone crisis and the covid-19 pandemic. This network also helped establish German manufacturing exports dominance—including direct exports to China. For their part, central and eastern European companies benefited from the connection to German firms possessing a global presence and they thus entered international value chains. For example, from 2004 onward, the import of car parts from the central and eastern European region into Germany was highly correlated with German passenger car exports to China. For some central and eastern European countries, the intra-global value chain trade also dominated their bilateral trade relationships with China—for example, SUV exports from German-owned factories in Slovakia made up to 78% of the country’s total exports to China.

The picture was not rosy for all network participants: central and eastern European companies bumped up against the growth limits inherent to supplier over-specialisation and often struggled to move up the value chain. Still, overall the region bandwagoned successfully on Germany’s global export success, driving growth and economic convergence.

Cars, cars, cars

Of all industries in the central European industrial heartland, the automotive industry is the crown jewel. It generates 9% of GDP and 26% of industrial production in the Czech Republic; more than one-third of all Czech exports goes to Germany. In Slovakia, the car industry generates 9.2% of GDP and roughly half of all industrial production; 43.4% of total Slovak exports to Germany are cars and car parts.[2] Automobile production is not just any other sector, but the essential industry in central Europe.

Any threat to Germany’s car industry could thus have severe impacts throughout the network. And German firms are indeed at risk—of being crushed under the weight of Chinese state-backed economic power, by losing market share in both Europe and China. The intricate dependencies in the central European heartland mean the risk of a “Detroit moment” is real.

The German auto industry’s China addiction

German carmakers move into China

“The future of Volkswagen will be determined by China”, declared Herbert Diess, then CEO of Germany’s largest automaker, in 2019. He might as well have said that the future of Volkswagen will be determined by the Chinese Communist Party.

Germany’s auto sector has been dependent on sales and production in China for at least the last 20 years. The sector adopted a two-pronged approach: one prong was to send direct exports to China from the European industrial base (often for high-end cars, machinery and auto parts); the second was to rapidly scale up direct investment in China itself to build out a regionalised value chain there.

Starting in the 1980s, German carmakers were among the first foreign companies to gain a foothold in China. The operating principle was the joint venture, which was a perquisite for foreign automotive companies to gain access to the growing Chinese market in exchange for transferring technology and knowledge. Hailed as a massive success for both sides, the idea emerged of cooperation that knows only winners and no losers.

German automobile manufacturers and suppliers have since established more than 350 sites in China. But the rapid growth in Chinese GDP and market sales concealed the structural challenges to the German position. Chinese joint venture partners absorbed know-how, and China’s automobile production matured rapidly in the 1990s with increasing localisation of component production. In 1992, China’s annual car-making capacity exceeded 1 million units; by 2000, this number had doubled. The country’s accession to the WTO further opened up its automotive market. China reduced tariffs on imported cars and gradually removed obligations that had set minimum percentages of Chinese-made parts in car production.

Alongside these developments, the burgeoning Chinese middle class’s increased demand for personal vehicles meant German car manufacturers invested heavily in making German cars in China. Chancellor Angela Merkel’s visit to the Daimler joint venture in Beijing in 2008 embodied the enthusiasm for stronger ties between “Made in Germany” and “Made in China”.

Chinese buyers begin to buy Chinese

By 2009, China had overtaken the US as the world’s largest automotive market for sales. In the same year, the Chinese government began to subsidise “new energy vehicles” (NEVs), which include battery electric vehicles, plug-in hybrid electric vehicles and fuel cell electric vehicles. It also began a targeted effort to promote domestic technological progress in the industry.

The government later intensified these policy efforts and wove them into key national strategies such as “Made in China 2025”, “dual circulation”, and “dual carbon”. These strategies also served as political campaigns to rally local governments, companies, research institutes and investors behind supporting the development of NEVs. The Chinese state’s strategic focus on NEVs paid off. While Chinese internal combustion engine vehicles never secured massive market shares—either in China or globally—in just six years, China had effectively leapfrogged the internal combustion era, which the West had allowed to drag on for decades. By 2015, China had become the world’s largest market for electric vehicles. Crucially, Beijing’s efforts had resulted in the development of a fully independent, cost-effective value chain.

This rapid transition caught the combustion engine-reliant German companies off guard. Their failure to fully embrace new technologies gave Chinese industry players—which had the policy backing of the Communist Party—a significant head start. Left with little choice but to localise their value chains in search of profits, market share and innovation edge, German auto giants have since embedded themselves even more deeply in the Chinese industrial ecosystem. They began investing in the increasingly impressive new Chinese carmakers, such as XPeng, and in Chinese battery manufacturers that were already dominating the sector. They used local Chinese suppliers over European parts producers and built fully integrated production systems, including R&D bases that serve not only their products in China but also globally. Since 2019, German carmakers have produced more cars in China than in Germany.

German companies continue to invest heavily in activity within China and believe in their ability to turn things around. In March 2025, then-CEO of Volkswagen Oliver Blume (long a part of the China story, who even received his engineering doctorate degree from Shanghai’s Tongji University in 2001), announced a new China strategy. He aims to secure 15% market share in the highly competitive Chinese market. This is a bold goal given that the overall market share of foreign car sales in China is falling steeply. Since 2022, German automakers have been facing an increasingly rapid decline in their market share in China. From 2020 to mid-2024, the market share of foreign car manufacturers dropped from 53% to 33%, with German brands among the hardest hit. In just one year, the share of German cars sold in China shrank from 20.4% in 2023 to 17.6% in 2024.

It is very unlikely that German market shares in China will bounce back, which will impact on the import of vehicles or parts made in Europe—with a significant effect on the supply chain in central and eastern Europe. In some cases—such as Seat/Volkswagen’s Cupra Mercedes-owned Smart cars, Renault’s blockbuster electric Dacia Spring made in China by Dongfeng, or Tesla—European and North American companies have already chosen China as a primary production site for exports to the EU. This has come at the expense of European factories. China’s state-backed automotive ecosystem has started to overshadow European car brands’ original industrial homeland.

China’s new role as competitor … and investor

The strength of Chinese car companies’ offer is undermining German sales in markets abroad. Chinese electric cars are able to offer feature-rich models with cutting-edge technology at extremely competitive prices. This has steadily eroded German companies’ consumer base.

The Chinese automotive industry continues to expand at a rapid pace. Sales of NEVs are forecast to reach 16.5 million units this year—a year-on-year growth rate of 30%. Domestic demand alone is expected to account for 15 million units, with increased government measures boosting consumer appetite, especially for NEVs. Chinese carmakers are on track to further strengthen their market share. Some companies have already recorded robust sale figures since 2025: for instance, XPeng delivered 30,350 vehicles in January—268% more than the same time last year. High market saturation has also forced manufacturers to engage in a fierce price war. In overseas markets, margins for Chinese producers are much higher, further incentivising an export-led growth strategy—to stay competitive at home.

China’s NEV production capacity is projected to reach 25 million units annually by the end of 2025. This far exceeds domestic capabilities in China to absorb this many new vehicles. In comparison, Germany annually produces a total of about 4 million cars—NEVs and internal combustion vehicles combined—Japan around 8 million and the US 10 million. Production capacity in China for NEVs alone will thus exceed combined production in Germany, Japan and America for all passenger cars this year. The level of excess production will continue to drive Chinese companies to seek overseas markets, particularly in Latin America, South-East Asia and the Middle East, but also in Europe. Having invested so deeply in China, German firms and the value chain that depends on them must now contemplate the stark reality of Chinese competitors in their home markets and Chinese investments in producing vehicles in Europe.

Europeans have not been unaware of the problem: as part of its wider policy of de-risking, the EU imposed tariffs on Chinese NEVs in 2024, which slightly reduced the market share of Chinese brands in the bloc to 8.5% by the end of the year. Nevertheless, some Chinese companies, such as BYD, have maintained steady growth in the EU despite the 17% tariff. They are now entering new markets within the bloc while building partnerships with car leasing companies. Britain has also become a popular destination for newly emerged Chinese auto companies; Chinese cars are projected to make up a quarter of this market by 2030. As Britain has no tariff barriers in place, its adoption of Chinese vehicles is much faster.

With additional tariffs making direct exports less profitable, the scramble for the European market is not just about selling cars made in China into Europe—but about moving into Europe. Numerous Chinese brands are considering localising final assembly in the EU. BYD decided to build its first major passenger car production facility in Hungary. Others, like Chery, pursue joint ventureswith local companies. The first Chinese electric vehicle to be made in Europe is already in production in Poland, in a factory belonging to Stellantis—a Franco-US-Italian automotive conglomerate based in the Netherlands—where Leapmotor’s assembly line was set up. Volkswagen had been rumoured to be in talks with Chinese companies on another leasing or sell-off arrangement for its worst-performing factories in Germany too.

However, this move into Europe is bringing little value added in terms of specialised jobs and innovation to local economies, including in the central European heartland. The first examples of production based in Europe—notably Leapmotor’s facility in Poland—show that Chinese companies prefer to import complete assembly sets (the so-called semi-knockdown mode) rather than involve local suppliers. It is also reported that China’s commerce ministry advised Chinese companies—both state-owned and private—to withhold technology and know-how from European partners.

For its part, the European Commission has proposed measures to “ensure foreign investments in the EU better contribute to the long-term competitiveness”. It proposed conditions such as additional demands for EU-sourced inputs, EU-based staff recruitment and technology transfers. The commission made these recommendations for the automotive and renewable industries—which suggests Chinese FDIs are its biggest concern in terms of localised value added.

Yet Beijing appears set on backing the export to Europe of fully built units—or the simple assembly of exported components—over truly localised production. It is therefore safe to assume Chinese companies will seek to leverage the enormous advantage of their home production base rather than use investment in Europe, including the central European heartland, to boost local economies there.

How the heartland could fall

If current trends continue—with Europeans mounting no immediate and resolute policy response—the second China shock could ravage Europe’s industrial landscape. The vertically integrated supply structure of Chinese automotive companies, combined with economies of scale at home, allows them to produce NEVs at significantly lower cost than their Western counterparts.

In China, big European brand names may become increasingly “domesticated” within the Chinese industrial ecosystem, sinking into dependencies and loyalties that will firmly tie the fate of these European companies to China, and to the wishes of the Chinese government. At the same time, as Chinese firms move into Europe—and with no obligation to invest, create jobs locally or share technology and know-how—Europe’s industrial heartland risks shrinking and turning into assembly lines for components made in China.

In Europe, European brands could become ever-more dependent on Chinese components made in Europe. For example, Chinese battery giant CATL is already producing for Mercedes-Benz in Europe only for final assembly often with Chinese staff, while supplanting European players.

Central and eastern European countries have already begun a form of industrial hedging—seeking Chinese investments as the traditional European automotive value chain loses competitiveness and technological edge. Hungary has taken the notorious lead, with the aforementioned BYD facility in Hungary. Aiming to be the first to get Chinese companies to set up their production in Europe, Budapest started a detrimental race to the bottom in terms of political cosying up, as well as lowering social and environmental standards. In Slovakia, interest in the Chinese value chain is growing. In late 2024, the prime minister, Robert Fico, welcomed a €1.4bn Chinese battery investment announcement, saying “Gotion’s investment in Slovakia will be one of the turning points in the relationship between China and Slovakia”.

Poland too is trying to hedge against the downfall of the European car giants and salvage the value chain via technological partnerships with China. It is keen on localising more of the value added—sometimes by playing hardball with Chinese counterparts by voting for the EU’s tariffs on electric vehicles.[3] The state-owned ElectroMobility Poland is aiming to secure technological transfers, as well as coordinating and plugging local automotive suppliers into the value chains of Chinese car brands considering entry to the European market. The Polish approach relies on trying to create the conditions for technology and know-how transfers. However, without an EU-wide approach to this challenge, this goal may prove elusive.

In the absence of a massive and creative intervention by Europeans, the central European industrial heartland faces two scenarios. To a degree, both are already unfolding.

Scenario 1: Heartland atrophy

WHAT HAPPENS: The European car industry goes the way of the European solar industry—virtually driven out of existence by unfair Chinese competition. The central European industrial network effectively withers on the vine. It starts to atrophy through lack of investment, leading tothe silent death of thousands of local suppliers in Germany and central and eastern Europe. Carmakers begin to close down their factories in central Europe and Germany. This has major knock-on impacts for suppliers, factories and people’s jobs.

HOW IT HAPPENS: Intense competition with Chinese brands effectively pushes European firms out not only from China, but importantly also challenges them in third markets from Latin America to South-East Asia, locations they had hoped to compete in for future sales. This incentivises big European brands to place their R&D, component sourcing and ultimately export production within the robust Chinese ecosystem to stay globally competitive. From a vantage point in central Europe or the German Mittelstand, there is no major difference between whether a Chinese or German brand export from China to Europe—in either case, the region’s local suppliers will most likely be cut out of the value chain.

Scenario 2: A sinicised heartland

WHAT HAPPENS: Chinese companies take over existing central European industrial assets or set up their own in the region. These Chinese factories and associated facilities do not join the central European industrial cluster but focus on integrating components and technologies developed in China, largely with Chinese staff and technology kept separate from counterpart firms. Effectively, Chinese assembly lines spring up where once European manufacturing took place.

HOW IT HAPPENS: With industrial atrophy progressing, businesses and political leaders in central and eastern Europe become increasingly attracted to working directly with Chinese firms in order to protect their automotive sectors. This becomes more likely after German firms follow the lead of cases such as Stellantis and Volkswagen and “sinicise” the European value chain. They do this by lending European factories to Chinese producers and by purchasing core technology components in ever-greater quantities from Chinese companies. These firms make a limited contribution to local economies. They import Chinese assembly sets, meaning value added is ultimately created only in China, where the most lucrative parts of the value chain, such as the manufacturing, technological design, marketing and sales are located.

*

In both scenarios, worries about the future of the automotive industry (in some cases, effective automotive monocultures in parts of the region) enter political and populist discourses. A major policy rift between Berlin and central and eastern European capitals opens up as political leaders allocate blame. The risk emerges that German politicians and trade unions push automotive brands to sacrifice production in neighbouring states in favour of keeping production in Germany—and China.

Make the Germany-central Europe value chain great again

Europeans still have time to avoid the atrophy and sinicisation of their industrial heartlands. But they must move quickly and decisively on a number of fronts.

Maintain and increase tariffs

Firstly, the EU must reinforce its trade policy by maintaining or increasing tariffs on Chinese electric vehicles, and potentially extending these to other types of cars and automotive components. However, given the rising competitiveness of Chinese cars made in China—and the presence of Chinese manufacturing within Europe—higher tariffs can only buy Europe time. They cannot solve more fundamental competitiveness problems. After all, the central European industrial cluster was born to compete on a global stage. It needs to become system-competitive.

Adopt a “Team Europe” approach

Next, the EU, member states and key businesses should jointly increase investment in domestic battery production and R&D for next generation batteries. This is to regain an edge in core technologies that are enabling China to corner this market. They should expand initiatives such as the European Battery Alliance and IPCEI (cross-border projects of EU-wide interest), and foster and increase funding for cross-border research collaboration between European carmakers and research institutions. The EU should also secure long-term agreements for critical raw materials and co-develop battery technologies through partnerships with resource-rich allies such as Australia and Canada. These steps can lead to a more resilient European presence in the global electric vehicle landscape, reducing dependency on China for key components such as refined graphite and lithium. These steps would help insulate the central European industrial heartland from Chinese coercion.

Focus on regional powerhouses

European policymakers should focus on existing regional powerhouses—like the central European industrial heartland—and make a bold move on integration and experimentation, complementing the EU-wide actions. Rampant subsidies certainly provided China with a head start, but now its industrial champions benefit from their own extremely robust, flexible and integrated industrial network of suppliers. For example, this enables Chinese carmakers to achieve extremely rapid production cycles—they are able to produce new car models in several months rather than years—and deploy innovation fast, as with the famously quick introduction of the DeepSeek AI application into Geely cars. Europeans should recognise that they already have the basis to create something similar.

Industrial policymakers across the EU should therefore work to develop an integrated European supply network. They should work across borders to capitalise on the EU-wide framework for a competitive advantage. This will demand further deepening of the EU’s internal market, following Mario Draghi’s calls for lower internal barriers and further opening up of the services sectors. But European decision-makers also need to internalise what every European company knows already—that the single market and everything it comprises competes as a system, not as individual member states. This demands collective, systemic action.

The best way to start is to think in terms of existing industrial clusters. Crafting policies focusing on cross-border regional value chains could help build bottom-up solutions. European decision-makers will succeed in this if they shape policy around how the economy is actually structured: not as a collection of isolated nations, but through deeply interconnected regional production networks that transcend national borders, involving hundreds, if not thousands, of companies. As noted, in specific sectors like cars, green technology and semiconductors, these value chains are highly regionalised, with tight interdependencies among certain member states. Fostering deeper industrial policy coordination along these established networks could take place, for example, through the creation of cross-border industrial strategy groups at the level of economy ministries. This should include industry representatives from the countries involved, to help break open national silos and foster a more European conversation in light of the major challenge from the outside.

Create a Heartland Economic Zone

In central Europe, Germany and neighbouring countries need to help each other before the consequences of the second China shock rips apart their deep level of economic integration. The ideal solution would be an immediate bold step towards perfecting the single market, but this takes time and speed is crucial. As an interim approach, a smart mix of EU-wide initiatives (such as those outlined above) combined with—importantly—a coordinated set of national measures could help the whole regional industrial network regain strength. This coordinated set of measures should come in the form of a special economic zone for projects of European interest. This could provide the missing piece in the EU’s attempt to regain competitiveness globally.

Special economic zones were a central ingredient in Deng Xiaoping’s China growth miracle. They served as powerful hubs for experimenting with market mechanisms, acting as incubators for industrial ecosystems and places for economic, social and policy innovation. Western Europeans may be less familiar with the European version of special economic zones, but these have been part of European policy processes for a long time, including in Latvia, Lithuania and Poland. Designed as regional aid and investment mechanisms in the post-cold war integration of eastern Europe they have mainly met regional development purposes. They allow exemptions from strict state aid rules within the single market for particularly deprived regions in need of special assistance.

The traditional European approach to special economic zones was to catch up, rather than charge ahead. Yet now a mindset shift is needed. With the help of the EU, Germany and central and eastern European countries should set up a trial version of special economic zones that extends across borders. This would create competitiveness incubators, labs and bulwarks against non-market competition. In terms of particular policy prescriptions, Germany and its neighbours do not need to reinvent the wheel, but can rather be quick and resolute in implementing many of the EU-wide proposals on regaining competitiveness. Those include the Clean Industrial Deal proposals, the Competitiveness Compass and ideas contained in the Action Plan for the European automotive sector. The European industrial heartland should be a spearhead for these EU-wide policies, in a region-wide coordinated effort to implement these policies. This will not only guarantee that the principles of the single market remain intact, but that they can also spark a virtuous “race to the top” among member states.

The Heartland Economic Zone must be international and not parochial; innovative, attractive and agile—but most importantly it must be cross-border in nature and capitalise on existing industrial clusters. It would be a special economic zone that is non-discriminatory and open to any global company—including Chinese—willing to stick to a commonly agreed set of terms and transparently abide by strict rules, including on data and cybersecurity (which would require changes in China’s domestic legislation). If a company from a like-minded country brings in a business model that does not depend on subsidised component imports, it should be free to invest and get all the benefits—no matter if it is European, American, from the Indo-Pacific or elsewhere.

How to build the Heartland Economic Zone

Coordinate industrial policy: The special economic zones can be labs for industrial policy coordination and harmonisation, and provide a platform for working-level dialogue between economy ministries and other relevant stakeholders. All countries involved should establish a taskforce at the ministry of industry level and a feedback loop to key local policymakers and industry leaders, from the big automakers to small and medium sized enterprises within Germany and central and eastern European states.

Harmonise labour law, environmental law and tax provisions within the zone: The countries involved should establish a commission for joint deregulation and standards and for digitalisation of processes. This may constitute a regionalised push within this limited zone for reducing intra-EU barriers, especially in the services sector.

Agree conditional support for FDIs and state-aid: Governments (both central and local) should extend support in terms of tax breaks, direct subsidies and land. They should make this conditional on the amount of localised value added, the number of central European supply networks involved, and the extent to which R&D capacities will be located within the zone.

Build high value added digital services ecosystems: The German government could consider explicitly supporting investments in the vast IT sectors in neighbouring countries, especially Poland and Romania. This would help develop digital services for the automotive industry, and a joint venture capital investment fund nurturing specialised start-ups can be created. So too could a joint network of autonomous driving testing infrastructure, which would also help with building a resilient European basis to meet cybersecurity standards, which the European Commission is currently working on for connected vehicles. This is already reflected in the 5G toolbox approach and enhanced software development in Europe, reducing dependence on both China and the US. A limited approach has been taken in Britain already: Chinese connected vehicles have been banned from some military facilities, but no comprehensive regulation is in place.

Make creative use of cohesion funds and IPCEI: Governments of central and eastern European countries should steer their EU cohesion funding into the automotive industry; specifically, in the parts of the value chain that have the highest growth potential. German companies and institutions, such as the economy ministry and the business associations, should work to involve more central and eastern European companies and institutions in related IPCEI funding, research and innovation consortia.

Make R&D structures more collaborative: Much of the R&D in the central industrial network is concentrated in German carmakers, leaving too little space for central and eastern European companies to grow. Germany and central and eastern European countries should therefore work together to more evenly distribute R&D activities so as to provide more competitiveness to the whole system; more knowledge-intensive supplier networks mean more flexibility and innovation.

Attract Chinese localisation of battery suppliers. Europeans need to make the considerable weight of the single market economy felt at the negotiating table but currently individual member states lack sufficient power to really negotiate with China. They need leverage to negotiate technology transfer, and must create a framework that enables them to consider Chinese investments from a position of strength, not from a position of weakness. To do this, greenfield investment should be subject to investment screening as suggested by the European Parliament. Additionally, Brussels should coordinate with member states to create attractive conditions through tax breaks and energy price subsidies for non-Chinese battery manufacturers from Japan or South Korea at the European level.

Assemble a heartland coalition of the willing

To support the introduction and strengthening of a heartland economic zone, political support is essential. This should take the form of a coalition of the willing: in the first instance, the more EU-orientated governments of Germany, the Czech Republic, Poland, and the Baltic states may be naturally more inclined to cooperate. Hungary’s approach, a race-to-the-bottom attempt to invite Chinese car production FDIs, puts Budapest in an opposing camp. Slovakia under Fico may soon follow suit. If such a coalition got off the ground, its progress could be expedited given the desire to simplify rules and procedures at the European level. Its members should conclude this simplification work in under two years in order to have an effect and actually bring value added to the region. In time, this could incentivise Hungary and others to reconsider their position. The prospect of reducing one’s industry to a Chinese assembly line is never going to be an attractive sell to domestic voters.

Apply new thinking to Europe’s other industrial networks

The Heartland Economic Zone can serve as an inspiration for other sectors of clean technology manufacturing in Europe. For example, a “High North Competitiveness Zone” for the wind industry could bring together Denmark and Germany for manufacturing, research and innovation focused on offshore wind. A “Sun State Competitiveness Zone” concentrated on hydrogen and electrolysers could be set up in Spain and Portugal.

Don’t forget the basics

For this vision to be realised, Europeans must recall the wider context and impose two preconditions: one that protects European industry on the import side and one that operates on the investment side.

Impose tough import restrictions on Chinese cars

With the constant influx of subsidised car and component (such as batteries) imports from China, attempts to “regain competitiveness” for Europe will be futile. Any response will have to include a German embrace of tariffs and demands a leap of faith for many car brands that fear short-term retaliation from China (or their own Chinese board members).

Provide no European state support for China’s “assembly line” manufacturing

For a fair and level-playing field, Chinese companies should be excluded from any government help and benefits from the Heartland Economic Zone if their FDI business model is based on subsidised component imports or merely the production of assembly sets. Serious concerns of this kind led the European Commission to use the foreign subsidy regulation instrument to investigate the BYD production plant in Hungary. If Chinese companies are allowed to leverage their subsidised financing and production ecosystems into their production in Europe, it will undercut all EU efforts to regain competitiveness at home.

Europeans can even turn the tables: they should use Chinese investments in the EU in key technologies—particularly in the battery sector—as a means to sharpen Europe’s competitive and technological edge. In pursuit of this, local content regulations and the inclusion of the local supplier base need to be thoroughly scrutinised across the entire EU so that Chinese companies do not violate the EU tariff regime. Financial transparency has to be rigid in order to uncover hidden subsidies and ownership structures. As the European Commission recently proposed, member states could collectively decide to make any state aid contingent on know-how and technology transfers, the inclusion of EU-sourced inputs and EU-based staff recruitment. Cybersecurity criteria for all connected vehicles imported into the EU would require rigorous application.

Escape forward to bypass Detroit

In the coming years—if not coming months—decisions made by Germany policymakers and German businesses—whether the big car companies like Volkswagen, Mercedes-Benz and BMW or key suppliers such as Bosch, Leoni and others—will have a major (potentially devastating) impact on society and politics in their own and neighbouring countries. If the automotive industry were to disappear from central and eastern Europe because of decisions taken in Berlin, at best this will further undermine faith in effective German leadership in the region, and potentially beyond. At worst, it will fuel resentment and populism in the places affected by accelerating deindustrialisation. There is no inevitability about German and central European industry going the way of Detroit, with all the sense of loss and resentment that arguably led to today’s Trump moment. But decision-makers would be wise to act now to ensure it never happens.

About the authors

Jakub Jakóbowski is deputy director of the Centre for Eastern Studies (OSW). He specialises in China’s foreign economic policy as well as China’s presence in Europe and the post-Soviet space.

Janka Oertel is director of the ECFR Asia programme, focusing on Chinese foreign and economic policy, EU-China relations, and green and digital transitions.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Alicja Bachulska and Sonia Li at ECFR and the Central European Department at OSW for their fantastic research support and Adam Harrison at ECFR for his amazing editing support and Chris Eichberger and Nastassia Zenovich for their brilliant graphics. This paper is part of the project “Central and Eastern Europe and the Future of the European China Debate” generously supported by Stiftung Mercator.

[1] International Trade Centre, Trade Map, available at trademap.org/Index.aspx.

[2] International Trade Centre, Trade Map, available at trademap.org/Index.aspx

[3] Based on authors’ conversations with European policymakers.

The European Council on Foreign Relations does not take collective positions. ECFR publications only represent the views of their individual authors.