China strengthened its grip on global clean‑energy supply chains in 2025, taking about a 70% share in each of the electric vehicle (EV) and battery sectors, while US energy policy under former president Donald Trump continued to prioritize oil and gas.

China accounted for 70.3% of global new-energy vehicle sales in 2025, according to the China New Energy Vehicle Industry Development White Paper (2026), jointly released by the Beijing-based Yiwei Institute of Economics (EVTank) and the China Battery Industry Research Institute.

The report said global new-energy vehicle sales reached 23.54 million units in 2025, up 29.1% from a year earlier. In 2025, new-energy vehicle sales in Europe grew 30.5% to 3.77 million units, while sales in the United States rose 1.72% to 1.60 million units.

The report said EV sales in the US barely grew as federal tax credits expired, with monthly sales in the final three months of 2025 dropping to about 80,000 units and market penetration at 9.6%. In Europe, sales outperformed expectations, led by a 43.2% rebound in Germany and growth of more than 30% in the UK to over 700,000 units, lifting regional EV penetration above 20%.

The report forecast global new-energy vehicle sales of 28.5 million units in 2026, including 19.8 million in China, rising to 42.7 million worldwide by 2030, with overall penetration exceeding 40%.

China also dominated the global power-battery market in 2025. Chinese companies accounted for 69.4% of global power-battery installations in the first 11 months of last year, up more than three percentage points from a year earlier, according to data released by South Korea’s SNE Research on January 6, with six Chinese firms ranking among the world’s top 10 suppliers.

- No.1 CATL: 38.2% global market share

- No.2 BYD: 16.7%

- No.4 CALB Group: 4.9%

- No.5 Gotion High-Tech: 4.3%

- No.8 EVE Energy: 2.7%

- No.9 SVOLT (Honeycomb Energy): 2.6%

These trends, together with US President Donald Trump’s early‑January move against Venezuelan dictator Nicolás Maduro in pursuit of overseas energy resources, prompted Dang Wang, a research fellow at the Hoover Institution at Stanford University, to argue that the global energy and manufacturing balance is shifting decisively toward China.

In an opinion article published by The New York Times titled “Trump Is Obsessed With Oil, But Chinese Batteries Will Soon Run the World,” Wang says China’s advance in batteries and electrification is reshaping global competition in ways that oil‑focused strategies struggle to address.

Wang says Trump has framed access to foreign oil as a central pillar of US power, betting that global demand for fossil fuels will remain strong for decades; by contrast, China has focused on substituting electricity for oil, using EVs and batteries to reduce domestic oil dependence while expanding exports of electrical products.

“In 2025, 54% of new cars sold in China were either battery-powered or plug-in hybrids,” he says. “That is a big reason that the country’s oil consumption is on track to peak in 2027.”

“China isn’t just building gigantic amounts of power; its businesses are reshaping technological foundations to electrify the world,” he says, adding that China’s lead rests on its ability to build power generation and manufacturing capacity at scale.

Tariff reductions

Europe has emerged as a key overseas market for Chinese-made electric vehicles since the US imposed a 100% tariff on the products in May 2024, effectively shutting them out of the US market.

In October 2024, the EU imposed anti-subsidy duties on Chinese-made EVs, setting additional tariffs of 17.4% on BYD, 20% on Geely, and 38.1% on SAIC, on top of the bloc’s standard 10% import tariff on passenger cars.

Analysts have said Chinese EV manufacturers, benefiting from relatively high margins and cost advantages, have been able to absorb the added charges without significant difficulty. Besides, these companies can set up factories in Europe to assemble their EVs, thereby avoiding tariffs.

The European Commission said on January 12 that China-based EV makers could seek to replace EU tariffs by committing to minimum selling prices set for each model and configuration, based on the price charged to the first independent buyer in the EU, while taking into account Chinese investment in local production.

“This is conducive not only to ensuring the healthy development of China-EU economic and trade relations, but also to safeguarding the rules-based international trade order,” said China’s commerce ministry.

Canada, an oil-rich country that Trump has publicly suggested should become the 51st state of the US, announced last week that it would lower tariffs on Chinese electric vehicles to 6.1%, the most-favoured-nation rate, from 100%. Ottawa also said it would allow imports of up to 49,000 Chinese EVs.

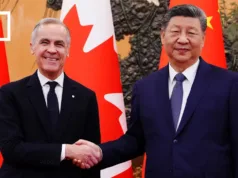

In return, China is expected to cut tariffs on Canadian canola oil to 15% from 85% starting March 1. The deal was reached during a January 16 meeting in Beijing between Chinese President Xi Jinping and Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney.

US Transportation Secretary Sean Duffy criticized the move, saying he believed Canada would eventually regret allowing Chinese cars into its market.

The United Kingdom, which is no longer part of the EU’s trade regime after Brexit, has never imposed additional tariffs on Chinese EVs. A decade ago, Transport for London (TfL) started using BYD’s electric buses. As of last June, it has deployed 2,000 units.

Data show that battery EVs accounted for 19.6% of new car registrations in the UK in 2024. The EV penetration rate in the UK was 21.57% in the first half of 2025, above the European average of 17.47%.

Breaking up alliances

Since 2024, Beijing has used trade deals and market access to test Western coordination aimed at restraining China’s EV sector. Some observers say differing political priorities and commercial interests among allied economies are increasingly complicating a unified response.

Several economists affiliated with the Paris-based Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) say in an article on January 8 that replacing tariffs with price floors would be a mistake for the EU. They argue:

- a price floor would keep consumer prices artificially high, transferring income from European consumers to Chinese producers;

- it would eliminate about €2 billion (US$2.2 billion) a year in tariff revenue, creating a direct fiscal loss;

- enforcement would be complex and vulnerable to disputes or circumvention, a structure that Chinese exporters would prefer to tariffs.

Some Chinese commentators argue that ending EU tariffs on Chinese EVs would be a pragmatic choice.

“The EU has never been truly unified on the issue, and its divisions became more visible in 2025,” says Shi Meimei, a Henan‑based columnist.

“Germany is the most clear‑headed due to the deep interests of Volkswagen and BMW in China,” she says. “France has talked tough but quickly felt pressure after Chinese countermeasures hit its agricultural exports. Eastern European countries also do not want to commit to the curbs against Chinese EVs.”

She says Europe’s weak economic backdrop has further limited its room for confrontation with China, citing the bloc’s high energy prices, inflation and near‑stagnant growth.

Read: Chinese EV firms can absorb EU tariffs: expert

Follow Jeff Pao on X: @jeffpao3