For decades, the global auto industry’s balance of power looked like a familiar story: western companies — Detroit, Stuttgart, Tokyo — led in engineering, pace, and prestige, while China played catch‑up. Today that narrative has flipped.

A recent Financial Times reporting tells how legacy carmakers in the United States, Europe, and Japan are openly studying, adopting and even copying Chinese practices to cut the time it takes to develop and launch a new car. It’s a striking tableau shift: the East setting the pace, the West racing to keep up. How the table has turned.

At the heart of this transformation lies speed. In China, EV makers routinely take roughly 18 to 22 months to conceive, engineer and release a new model, sometimes in market‑ready form faster than Western rivals can get their blueprints approved. That’s about half the typical development cycle seen in Detroit or Wolfsburg, where traditional processes stretch 32–48 months or longer.

Where the casual eye sees only marginal efficiency gain, industry executives see a strategic lifeline. During an InsideEV podcast not very long ago, General Motors’s president publicly stated that Western automakers must learn from Chinese rivals to quicken their model pipelines and stay competitive, while admitting that “copying each other and trying to price each other out of the market [isn’t] necessarily a great thing.”

“I would say we can learn a lot from the [Chinese] speed,” he said.

Why China Has the Jump

Several structural forces power China’s advantage. Chinese firms often control more of their supply chain and components in‑house or through tightly coordinated local suppliers. This trims sourcing delays and reduces cross‑border engineering lags.

Advanced simulation tools and software‑based testing cut the need for long road-testing cycles. Virtual validation and over‑the‑air updates further compress the path from prototype to production.

Six‑day workweeks and nimble decision structures (flatter hierarchies and empowered teams) let Chinese automakers make rapid, market‑driven choices that would take months of committee meetings back in the West.

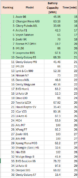

Taken together, these factors have helped Chinese carmakers double their global footprint in electric vehicles while many foreign brands shed market share at home.

Western Automakers Take Note — And Act

What was once a one‑way flow of technology and expertise — Western cars exported to China, Chinese firms farming design tricks from Europe and Japan — is now reversed. Executives from Ford, Volkswagen, Nissan, Renault and other legacy groups have all described explicit efforts to adopt Chinese methods to accelerate product cycles.

Ford has partnered with Renault to co‑develop small electric vehicles in Europe using a methodology honed in Shanghai that trims development time to under two years.

Volkswagen reports slashing EV development timelines by roughly 30% for China‑market models by leveraging local suppliers and digital workflows that echo Chinese practices.

Nissan launched its affordable N7 electric sedan after roughly two years of development in China with Dongfeng in a pace that would have been unimaginable a decade ago.

These tactical tweaks underscore a deeper cultural shift toward iteration, modular design, closer supplier integration and regionalized R&D.

Table Turns — And Tensions Rise

The implications stretch beyond product cycles. Western policymakers worry not just about losing market share but about strategic dependence. In the United States, for example, concerns are growing that China’s lead in EVs and batteries carries national security risks.

In Europe, regulators are debating how to force legacy automakers to stay relevant without retreating from emissions targets, an argument that exposes how Chinese momentum is reshaping Western policy debates.

Some analysts question whether the rush to match China’s tempo might compromise quality or safety. After all, shorter testing cycles can mean more reliance on software patches post‑launch.

But for legacy automakers, the calculus is stark: adopt the Chinese playbook or risk obsolescence. Ultimately, it stands to reason that the global auto industry is now not only wrangling with the elusive electrification but also sprinting to adopt the Chinese way of making cars: faster, leaner, and more digitally native than ever before.