Support CleanTechnica’s work through a Substack subscription or on Stripe.

Most Western analysis of the automotive transition still carries a quiet but profound blind spot. China is often treated as one large market among several, occasionally acknowledged as the largest, but rarely internalized as the market that now determines global scale, cost curves, and learning rates. This is not a failure of intelligence or intent. It is a failure of mental calibration. The size of China’s car market, the speed of its electrification, and the resulting industrial consequences sit well outside the lived experience of most Western policymakers, analysts, and executives. The result is persistent underestimation of what China’s domestic battery electric vehicle market already implies for global exports and future market share.

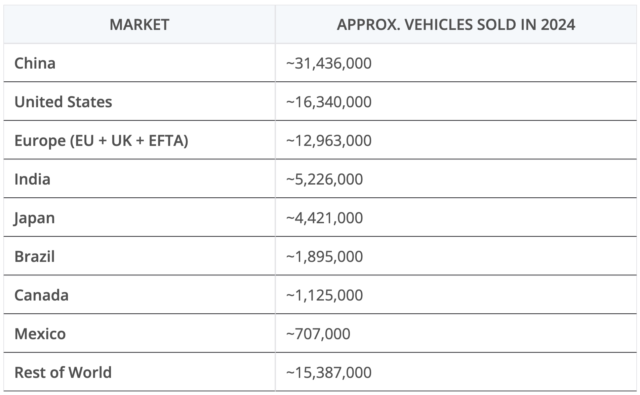

The first step in correcting this is to put global car markets on the same numerical footing. Global light vehicle sales in recent years have fluctuated between roughly 85 million and 90 million units annually. In 2024, the total was approximately 89 million. China alone accounted for about 31 million vehicle sales that year. The United States sold about 16 million. Europe, including the EU, UK, and EFTA, sold roughly 13 million. China did not merely lead. It sold more vehicles than the United States and Europe combined. This has not been a one year anomaly. China has been the world’s largest car market every year since 2009, and the gap has widened over time, not narrowed.

China is not just the largest market. It is the fastest electrifying market at large scale. In 2024, plug in vehicles accounted for roughly 40% of all new car sales in China. In late 2025, monthly plug in shares exceeded 50% in several months, with some months approaching 60%. In absolute terms, China sold roughly 13 million battery electric vehicles and plug in hybrids in 2024. That single country sold much more than double the plug in vehicles as the rest of the world combined. By contrast, the United States sold about 1.6 million plug in vehicles in 2024. Europe sold about 3.2 million. Percentages are often used to suggest parity or convergence. Absolute unit volumes tell a different story.

Volume matters more than policy statements because manufacturing economics are shaped by repetition and throughput. When factories run at high utilization year after year, unit costs fall through learning effects, supplier competition, yield improvements, and amortization of capital equipment. China’s domestic EV market is now large enough to keep dozens of battery cell plants, pack plants, motor plants, inverter plants, and vehicle assembly lines running continuously. That volume exists regardless of export conditions. It does not depend on foreign demand. It is internal, persistent, and growing. This matters because it anchors cost structures in a way no smaller market can easily replicate.

Batteries sit at the center of this dynamic. Battery packs remain roughly 30% to 40% of the manufacturing cost of a battery electric vehicle. China controls approximately 75% of global lithium ion cell manufacturing capacity. It refines more than 60% of the world’s lithium, over 70% of cobalt, and nearly all battery grade graphite. It also dominates lithium iron phosphate chemistry, which now accounts for more than half of all EV batteries sold globally. LFP batteries trade lower energy density for lower cost, longer cycle life, and reduced reliance on nickel and cobalt. These characteristics align closely with mass market vehicles. Battery pack prices in China fell to $84 per kWh at the pack level in 2025 for LFP systems, while Western manufacturers remain closer to $130 per kWh. That $45 per kWh gap translates to a $2,700 difference in a 60 kWh vehicle before margins.

China’s domestic EV market also functions as an accelerator for export readiness. Competition inside China is intense. More than 50 domestic brands sell EVs at scale. Margins are thin. Product cycles are short. Software updates, hardware refreshes, and cost reductions occur continuously. Vehicles that survive this environment tend to be mature by the time they are exported. By contrast, many Western EVs enter the market at higher price points with lower volumes and longer iteration cycles. This difference shows up in reliability data, feature completeness, and pricing flexibility when vehicles reach third markets.

Exports from China are already large and growing. In 2024, China exported approximately 5.9 million vehicles, up from fewer than 1 million in 2020. Of those exports, roughly 40% were battery electric or plug in hybrid vehicles. China is now the world’s largest vehicle exporter by volume, surpassing Japan. This fact is still not widely internalized in Western discourse, which often frames Chinese exports as a future threat rather than a present reality. These exports are not limited to Europe. They are concentrated in Southeast Asia, the Middle East, Latin America, Eastern Europe, and parts of Africa. Many of these markets are price sensitive and lack strong domestic automotive manufacturing bases.

Japan’s export model is the most exposed to growing Chinese EV exports. Japanese manufacturers export roughly 4.0 to 4.2 million vehicles annually, a large share of national production, and those exports are heavily concentrated in price sensitive markets where Chinese EVs are scaling fastest. Japan’s domestic EV penetration remains below 3% of new sales, which limits battery scale and slows cost reduction. Hybrids dominate Japanese electrification strategy, but hybrids do not compete directly with battery electric vehicles on drivetrain simplicity, energy cost per kilometer, or long term maintenance. As a result, Japanese ICE and hybrid exports face direct substitution risk in markets where Chinese EVs already offer lower total cost of ownership. Without a rapid increase in domestic BEV volume, Japanese exporters struggle to match Chinese pricing without eroding margins, making this export position structurally vulnerable.

Europe, treated as a bloc, exports approximately 5.0 to 5.5 million vehicles per year, but the composition of those exports differs from Japan’s. A significant share comes from premium and near premium segments where brand still carries pricing power, especially in wealthier markets. Europe’s domestic BEV penetration reached roughly 20% of new sales in 2024, which provides some battery scale and policy alignment. However, that scale is fragmented across many countries and manufacturers, limiting learning rate advantages. European exporters face rising pressure in mid priced segments and in emerging markets where brand matters less than upfront price and operating cost. There are two additional threats worth noting. The first is that the rest of the world is increasingly seeing Chinese brands as having the same cachet as legacy European brands, and the second is that Chinese OEMs have bought many European brands such as MG and Volvo. Brands are just marketing, not manufacturing. Europe is less likely to see an abrupt collapse in export volumes, but more likely to face margin compression and stalled growth as Chinese EVs expand across third markets.

South Korea exports approximately 2.7 to 3.0 million vehicles annually, with Hyundai and Kia accounting for most of that volume. South Korea sits between Japan and Europe in exposure. It has stronger EV momentum than Japan and more vertically integrated manufacturing than Europe, but far less domestic scale than China. Korean manufacturers compete effectively in North America and parts of Europe, but face growing pressure in Southeast Asia and the Middle East where Chinese EVs are increasingly competitive on price. South Korea’s export risk is not immediate displacement, but gradual erosion of price competitiveness in markets where Chinese firms can accept lower margins backed by larger domestic volumes.

Mexico exports roughly 3.0 to 3.5 million vehicles per year, but its situation is fundamentally different. Mexico is not a national champion exporter in the same sense as China, Japan, or South Korea. It is an export platform tightly coupled to the United States. The majority of vehicles produced in Mexico are sold into the US market under integrated North American supply chains. Mexican exports are therefore insulated from direct Chinese competition by trade rules and proximity, but also constrained by US demand and policy. The USMCA free trade deal linking North America’s three countries is up for renegotiation in 2026, and the renegotiation is in context of Trump’s global trade war and increasing US isolationism. Mexico’s exposure to Chinese exports is indirect, mediated through shifts in US strategy rather than global market competition.

Taken together, these exporters face very different risk profiles. China exports from a position of domestic strength and cost leadership. Japan exports from a position of ICE legacy and limited EV scale. Europe exports with brand strength but weakening price competitiveness. South Korea occupies a middle ground with some EV momentum but limited domestic volume. Mexico functions as a regional manufacturing extension rather than a global exporter. Understanding these distinctions is critical to understanding how China’s domestic EV market reshapes global trade flows rather than simply increasing export volumes in isolation.

The focus on whether Chinese vehicles can penetrate the United States or Western Europe misses the larger picture. China does not need dominance in those markets to grow its global share. If Chinese manufacturers capture incremental share across dozens of mid sized markets, the aggregate effect is substantial. A gain of 5% market share across Latin America, ASEAN, the Middle East, and Africa combined can equal or exceed gains from a single large Western market. In many of these regions, total cost of ownership matters more than brand legacy. Battery electric vehicles using LFP chemistry often deliver lower lifetime costs even where fuel prices are subsidized.

Trade barriers change the shape of this expansion but not its direction. Tariffs can slow direct exports and encourage local assembly. They can push manufacturers toward knockdown kits, joint ventures, or greenfield plants abroad. What they do not do is erase the underlying advantage created by battery scale, supply chain control, and domestic demand. When a Chinese manufacturer builds a factory in Thailand, Mexico, or Hungary, much of the value chain remains Chinese. Cells, modules, power electronics, and platform designs often continue to originate in China. The label on the vehicle changes. The industrial logic does not.

For Western automakers, this creates a narrow window of strategic choice. Competing on assembly alone is not sufficient. Battery scale, chemistry selection, and supply chain integration matter more than brand or marketing. Protection can buy time but not cost parity. Partnerships can transfer technology but often also transfer leverage. Specialization in premium segments can preserve margins but limits volume. None of these paths are inherently wrong, but all require acknowledging the scale of the challenge rather than minimizing it.

There are broader energy system implications as well. China’s dominance in EV production reinforces its position in stationary storage, grid scale batteries, and industrial electrification. As EV volumes rise, battery factories expand, driving further cost reductions that spill into other sectors. This feedback loop accelerates electrification beyond transport. It also tightens demand for critical minerals, shaping global mining investment and processing capacity. Countries without battery manufacturing scale increasingly find themselves price takers rather than price setters.

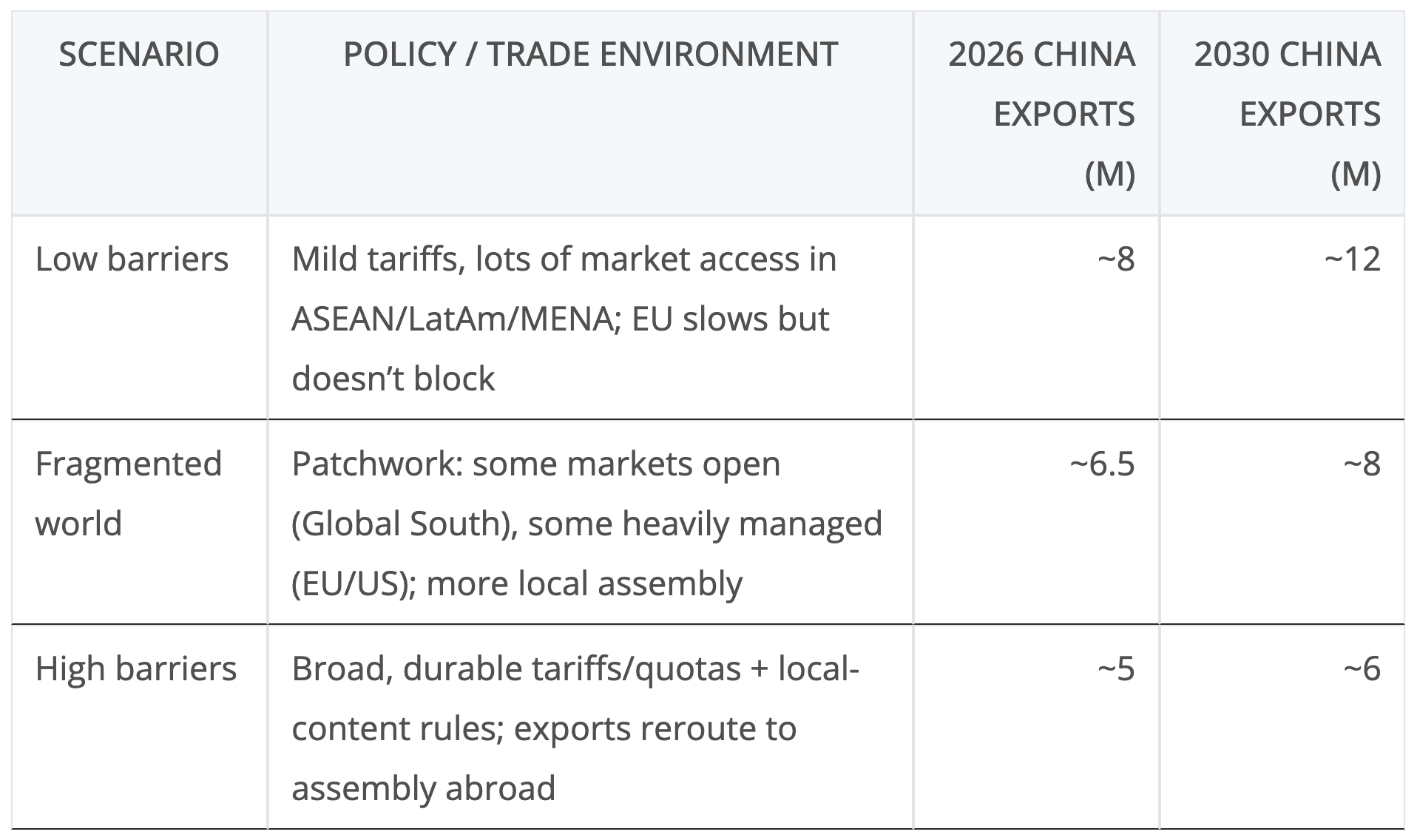

Below is a table of scenarios outlining potential paths for China’s share of global vehicle sales and exports under different trade and policy assumptions. In none of the realistic scenarios is China other than the globally dominant manufacturer and exporter of light vehicles. In none of them is the future of light vehicles other than increasingly electric. In none of them is current US policy particularly meaningful except to US consumers, who will pay higher prices for inferior vehicles while the world moves on without the USA.

Even in the high barriers scenario, Chinese components and local assemblage of Chinese cars in foreign markets will increasingly dominate the markets. The flywheel of China’s large domestic market, intensely competitive manufacturing, battery dominance, low price points and leading exports will deliver EVs globally regardless of significant barriers.

The common Western narrative frames China’s automotive rise as a future risk that might be mitigated with sufficient policy alignment. The numbers suggest a different framing. China’s domestic EV market has already crossed the threshold where scale compounds quietly. By the time this is widely acknowledged, the structure of the global automotive industry will already have adjusted. The question is no longer whether China will influence global car markets. It is how clearly others recognize that it already does.

Sign up for CleanTechnica’s Weekly Substack for Zach and Scott’s in-depth analyses and high level summaries, sign up for our daily newsletter, and follow us on Google News!

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Sign up for our daily newsletter for 15 new cleantech stories a day. Or sign up for our weekly one on top stories of the week if daily is too frequent.

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.

CleanTechnica’s Comment Policy